If anyone in St Bathans looked too closely, I would be dead before nightfall.

The light was kind to the place, which felt unfair, given what I was bringing back with me.

The town sat in the dying light as if the reckoning were behind it — the road dusted gold, the low buildings holding their shape, the air still warm enough to pretend the day hadn’t failed.

William turned in the saddle, taking it all in with the calm of a man who knew what would happen if I slipped.

“Well,” he said. “She’s gone to the dogs.”

I kept my eyes on the road. If I answered, he’d only keep going. Silence was meant to be discouraging. It rarely worked.

A man on the hotel steps paused with a broom resting against his thigh and watched us approach. He didn’t nod. He didn’t smile. He just looked — long enough to decide whether I was a mistake that had walked back into town.

I adjusted my grip on the reins, more force than was necessary. The horse flicked an ear back at me.

I said nothing.

“Mind you,” he went on cheerfully, mistaking endurance for interest, “they change often enough. Towns, men. Hard to keep up.”

I breathed out through my nose and tightened the reins again, this time deliberately. He didn’t need an audience. That was the trouble. He talked like the world was obliged to hear him, and more often than not, it did.

“You always choose places like this?” he asked.

“I choose shelter,” I muttered, because the word was quicker than explaining myself.

He smiled, slow and knowing, as if I’d said something else entirely.

“That’s what I mean.”

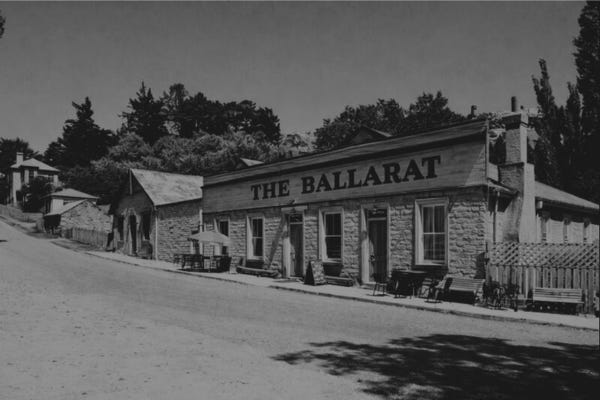

The Ballarat leaned into the road like it had been waiting — not for company, but for the same old story to come back around. Warm light bled from the windows, catching in the dust, turning the air the colour of old honey.

William didn’t need the invitation.

“Well, James,” he said, craning to look. “This is bold.”

I didn’t bother answering. The leather creaked when I dismounted. The ache had nothing to do with the ride and everything to do with the day refusing to end.

“You’re sure?” he went on mildly.

I reached for his reins.

“Places like this,” he added, “have long memories.”

I felt it then — the unnecessary pressure in my hands, the reins drawn tighter than the road required.

“Down,” I said, voice tight.

He smiled, already shifting his weight to dismount.

By the time I pushed the door open, the room paused. Not a hush — a settling. Like dust after a door closes in a long-empty place.

St Bathans knew how to keep old things close. Names. Grievances. Men who didn’t leave cleanly.

I felt the name James McLeod move through the room before I did — intact enough to bruise. Recognition came without welcome and no one moved to make room.

A man near the bar leaned back on his stool, eyes fixed on William’s wrists.

“You’ve no right to do that.”

I didn’t answer.

“Ain’t the law anymore, are you, James?” Tom, the publican, called from behind the bar. Not hostile. Just weighing me.

“I’m bringing him in.”

The words came out flat, the way you spoke when you didn’t want anyone to hear the shake underneath.

“On whose authority?”

I let my gaze settle on him — the man from the bar, red-faced, sleeves rolled, the kind who liked an audience.

“My own.”

That did it. A couple of men snorted.

“Thought you lost that,” the man said, grinning now, enjoying himself.

“That’s the point.” I kept my voice steady, though I could feel the room leaning in. “I’m putting it on record.”

I glanced around once — enough to count faces, not enough to invite challenge.

“I’m getting it back.”

Tom shook his head. “You don’t clear your name by playing constable.”

Margaret, his wife, stepped forward then — flour on her hands, smaller than I remembered, steady as stone. “You clear it by telling the truth.”

A glass rang softly as it was set down.

“And the truth,” she went on, pointing at me, “is that James McLeod was pushed out because he wouldn’t look the other way. Same as others. By the same men.”

Her husband started to speak. She didn’t look at him.

“He eats,” she said. “And the man he’s bringing in eats too.”

Her eyes held mine for half a beat too long.

Tom hesitated behind her. Face contorted with refusal. “Marg—”

“They’ll eat,” she said again, now with a tone that Tom and the regulars clearly knew and respected. “And they’ll stay.”

Chairs scraped. The man by the bar muttered. No one argued.

She turned back to me. “You look done in, James.”

The name landed softly. I nodded, because it was easier than speaking.

At the table, William looked around him with the air of a man out for a leisurely dinner, not a prisoner on the way to face justice. He glanced back at me and stretched his wrists with a theatrical wince.

“Circulation.” He rolled them again. “It’s important.”

“Shut up.” I didn’t lower my voice.

Margaret set the plates down, matter-of-fact. The smell of bread hit first, then stew — lamb, thickened with barley, the kind that asked nothing of you except that you stay.

She lingered. “How’s Amy?”

The name caught. Not hard — just enough to remind me where the edges were. I kept my eyes on the table, counted the places, the gaps.

William shifted in his chair. The cuffs clinked as he worried at them, slow and deliberate, as if he had all evening.

“She manages,” I murmured.

“And the children?”

“Growing.”

“Five now, isn’t it?” she asked — not accusing, not prying. Just remembering.

William snorted, quick and quiet.

She delayed, ladle hovering.

“And Jane?”

William’s spoon stalled halfway to his mouth.

“She gets by,” I let my eyes meet hers briefly, then lowered them, my throat tight enough that I didn’t trust another word.

Margaret nodded slowly. “You always were so similar.” Her gaze stayed on me now, distant but intent. “Hard to tell you apart when you were young.”

A fond smile crossed her face. “Folk used to get it wrong all the time.”

William lowered his spoon and smiled into his bowl, private and pleased.

Margaret lingered, as though something else had risen to the surface and refused to settle. I kept my eyes on the table, on the worn grain of it, gave her nothing to catch hold of.

She cleared her throat at last and turned back toward the bar.

William waited exactly long enough.

“Five children,” he said thoughtfully. “That’s a lot of enthusiasm for a man with… recent difficulties.”

I stared at my bowl. “Eat,” I said to him.

“Disgrace does things,” he went on. “Affects… performance, so I hear.”

I tightened my grip on the spoon.

“Though,” he added, generous now, “After five children, Amy’s probably grateful for the rest.”

I looked up then. He was smiling into his food, all innocence.

I set the spoon down carefully. “Another word,” I murmured, “and I gag you.”

He beamed. “Ha! I knew I’d find you in there, soon enough, James.”

“Eat,” I said again.

“Yes, sir.”

The word slid. I felt it anyway.

He’d always known how to find the softest part and lean there, smiling.

Around us, the room resumed its low hum. A man laughed too loud near the bar. Another tipped his glass and poured again. Outside, the light drained from the windows, leaving the warmth inside to fend for itself.

William ate slowly, deliberately, he always did. He tore bread with his teeth, chewed as if it deserved consideration, wiped his fingers on his trousers with care.

I finished first. When I stood, Margaret met my eye and came over.

“You’ll want the back room,” she said, holding out a key. “Quieter.”

I took the key. “Thank you.”

She hesitated, then reached out — not to touch, not quite — just close enough that I felt it.

“You were treated badly.” Her eyes were warm. “It wasn’t fair, what they did, what they said about you.”

I nodded once and pushed my chair back. “Thank you, Margaret.”

I took William by the arm and turned us toward the corridor. He came easily, compliant as ever.

“You know,” he murmured, once we were moving, “Margaret didn’t ask after me at all.”

“She didn’t need to.”

“No,” he agreed, as the floorboards narrowed and the noise from the bar fell away. “She always did like the McLeod twins best.”

We reached the end of the passage. I stopped, fished the key from my pocket, felt his attention settle again.

I pushed the door open.

He glanced at me then — not teasing, not smiling.

“You do choose rooms that don’t give a man many options.”

The room was narrow and spare. Two iron-framed beds, neatly made, a thin aisle between them. A washstand against the wall, the bowl chipped, the pitcher mismatched. The window looked out onto nothing of consequence — a yard of trampled dirt and the back of another building, close enough to touch if you leaned.

I took it in the way I always did. Distance to the door. The angle of the window. Where a man might stand if he meant trouble.

William waited, hands still bound, watching me with mild interest, as if this were all part of the accommodation.

I crossed to the window and tested it. It opened a handspan and no more. Enough for air. Not enough for a man.

“That one.” I nodded toward the bed by the window.

He went without argument, sitting and stretching his legs out, studying the room as if it had been chosen for his comfort.

“If I meant to run,” he observed, “I wouldn’t wait until you’d finished checking.”

I removed my boots, joints complaining, and set them beside the nearer bed.

“We ride at first light.”

He inclined his head.

“I won’t try tonight.”

I straightened.

“No?”

“No.” His mouth curved, faintly amused. “Wouldn’t help either of us.”

I poured water into the bowl and washed my hands. Dust lifted away in grey streaks.

“You think bringing me in puts things straight,” he said then, voice quieter. “That if you put the truth in the right place, it has to count.”

I dried my hands carefully.

“It puts it where it can’t be buried.”

William watched me for a moment.

“James McLeod had a reputation for believing that,” he said. “The Law.”

I kept my back to him.

“He thought if he followed the rules closely enough,” William went on, “they’d have no choice but to listen.”

The bowl trembled once in my hands before I steadied it.

“They didn’t,” he said.

I set the towel down.

“He wasn’t guilty.”

“No,” William agreed. “That was never the question.”

Silence settled. The lamp between us remained unlit.

“They’ll take me in,” he said at last. “Hold me. Write what they’re told to write.”

A pause.

“And when they’re done, they’ll say James McLeod followed procedure to the end.”

My jaw tightened.

“They’ll say he was wrong,” William finished. “But well-meaning.”

“That’s enough.”

“Is it?” His tone stayed calm. “Because you didn’t ride this far for well-meaning.”

I reached for the lamp.

“Sleep well, James,” he said softly — like a courtesy.

I paused with my hand outstretched.

Outside, the warmth had bled from the air. The town settled into itself, unchanged, indifferent.

I didn’t correct him.

And I lay awake longer than I meant to.

I woke before the light reached the window, the air still cool, my body already braced for the road. That moment before leaving — when resolve hardened into something you could stand on.

William was awake too. I’d known he would be. He sat on the edge of the bed, boots already on, elbows on his knees, hands loose. Waiting.

I checked the cinch of my coat, the weight of what I carried settling where it always did. Today would be harder. Today would ask for proof.

“We should go early,” I said. “Before the town stirs.”

He nodded. “You always liked to be ahead of things.”

I reached for my hat.

“It won’t bring James back.”

The words landed behind me. I didn’t turn.

“Marching me in under his name,” William went on, voice steady, “like it still belongs to him. It won’t undo what they did.”

“They don’t get to decide how his story ends.”

A pause. Then his breath left him slowly.

“No,” he said. “That’s why you’re here.”

Silence stretched between us.

“Clear his name first,” William continued. “Then tell them he’s dead.”

I turned.

He met my gaze without flinching.

“It’s the only way it works.”

Heat flared once — sharp and useless — then burned down to something steadier. I mastered it. Barely.

“You’ll answer for what you know.”

“Of course.” He rose, smooth as ever. “That’s why I let you bring me.”

The light crept in through the window, thin and pale. I lifted the hat and settled it back where it belonged.

Under another name, I would carry my brother a little further yet.

This piece was written in response to Bradley Ramsey’s Power Up Prompt. I took the Western setting and translated it to the New Zealand goldfields — the closest thing we had to a Wild West, with the same boom-and-bust towns, fragile law, and men who outlived their authority.