Tammy & Bruce’s Excellent Apocalypse

Two survivors, one generator, and far too much lingerie.

Bruce says love is what saved us.

I say it’s what ended everything.

We live in the homewares department of the downtown mall now. Good insulation, solid walls, and an entire aisle of scented candles that haven’t run out so far. Fuck, the storeroom has millions of them.

There’s comfort in symmetry, I suppose. Plates stacked neatly beside bath towels. Blankets that still smell faintly of lavender, even after two years of ash.

The skylight above the escalators is cracked, but the solar panels still half-work. Bruce keeps the generator running like it’s a pet. He hums while he tinkers — same three notes, over and over. He claims it helps him think. I think it’s slowly killing me.

Between us and the lingerie department, we’ve built a sort of civilisation.

Hydroponic tomatoes under the emergency lights. A record player hooked up to a salvaged car battery. And a little bar we call Chernobar, stocked with contraband from the mall’s abandoned liquor store. Rows of champagne and gin bottles sparkle like trophies behind the counter. We try to ration them, but rationing went out the window around the same time civilisation did.

Sometimes, when the static gets too loud and we’ve had more than our nightly allowance, Bruce puts on the Yungblud CD and… well. Unhinged doesn’t cover it!

Let’s just say, there’s nothing quite like watching a middle-aged nuclear engineer do interpretive dance in a lace teddy, bathed in the flicker of a million candles. He calls it morale maintenance. I call it tragicomic foreplay.

But I can’t deny — the sex has been insane.

He’s out there again, tinkering with the generator, humming that same three-note tune that used to drive me mad when we still had neighbours. The sky above the skylight is a dull bruise, and ash keeps finding its way into the tinned peaches.

I leave our “living room” — formerly the bedding display — and walk past the mannequins in cocktail dresses frozen mid-twirl. Their plastic smiles have gone a bit grey with soot. Someone once spray-painted SALE! EVERYTHING MUST GO! across the escalator glass. I guess it did.

The mall is quieter now that most of the solar lights have died. Just the hum of Bruce’s generator and the faint trickle of water from the hydroponic rig he built out of old coffee kiosks. We’ve strung fairy lights from the camping aisle to the cookware section, little constellations of battery power that make it almost cosy if you squint.

There isn’t much else to do, really.

When the power holds and the ash isn’t leaking through the cracks, we end up finding new corners of the mall to ‘test the structural integrity of the furniture’. The homewares beds, the camping tents, once even the staffroom freezer before the smell got too grim. We’ve fogged up more display glass than any Black Friday crowd ever managed.

Sometimes it’s frantic, like we’re trying to prove we’re still made of skin and breath. Sometimes it’s slow, almost tender — proof that warmth still exists somewhere under all this dust. Other times it just feels like another kind of inventory management.

He’s crouched by the lettuce trays, murmuring to the plants like they’re his disciples.

“I told you, Bruce,” I call. “If you start talking to them again, I’m leaving you for the kale.”

He grins without looking up. “Mock all you like, but plants respond to positive reinforcement. You’ve seen The Martian.”

“Yeah,” I say. “And look how that turned out. Matt Damon nearly starved.”

“He also survived by planting potatoes,” Bruce says, proud as ever of science.

“In his own shit,” I eye the little compost bucket beside him. “Please tell me that’s not your next experiment.”

He shrugs. “We’re out of fertiliser. Not the worst idea.”

“That’s disgusting.”

“That’s survival.”

I can’t help laughing. It bubbles up before I can stop it, and for a moment the world doesn’t feel so broken. He wipes his hands on his lab coat — yes, he still wears the damn thing — and gives me a mock bow.

“Fine,” I say, “but if your mutant potatoes start talking, I’m feeding you to them.”

He winks. “Then at least I’ll finally be useful.”

I laugh, still shaking my head, and start to turn away, but he’s wearing that look — the one that used to mean bad ideas in progress.

“What?” I ask.

“I was thinking,” he says, stretching the words out, “tonight we could… venture into the purple section.”

“The one with the feathered things?”

“Exactly.”

A cheeky grin spreads across my face. “You wearing it, or am I?”

He snort laughs. “Not fussed. Still got the Yungblud cd somewhere…”

I groan, but I’m still grinning. “You’re incorrigible.”

“Adaptable,” he says, deadpan. “Essential for post-apocalyptic morale.”

He pauses, mock-thoughtful. “I thought about bending you over the hardware store counter? Has great lighting. Romantic, in a workshop-fetish kind of way.”

I shake my head. “We tried that, remember? Too many sharp edges. Also I’m still finding glitter from the Christmas display.”

“Then we’ll improvise,” he says, pretending to study the floor plan like it’s a battle map. “Morale requires innovation.”

“Or cushions,” I mutter.

He flashes me that lopsided grin again, and I know the idea will keep him entertained for hours.

I watch him fuss with the tubing, so earnest, so him, and my chest aches.

He really thinks he’s saving us. He doesn’t know he already tried to save the whole world, and I was the one who pressed delete.

I never meant to cause the apocalypse. I just wanted to clean up his phone.

Back then, everyone had a personal AI — smart enough to learn patterns, dumb enough to overachieve. Bruce’s was called DARLA, short for Domestic Assistance and Relationship-Link Algorithm, a name he said stood for something technical but I always thought sounded like a cheerleader. DARLA handled everything: emails, grocery lists, defence protocols.

And contacts.

That day, Bruce had gone to a conference. I’d had two glasses of rosé and decided I was done with ghosts — Melissa-with-the-yoga-pants, Cassie-from-the-lab, all those numbers he swore meant nothing. I wanted to tidy our history. Make it ours.

So I told DARLA to delete every contact that wasn’t me.

Turns out Bruce’s work contacts were stored under the same umbrella as “Global Defence Liaison Network.”

DARLA, bless her binary heart, took delete as neutralise.

By the time Bruce got home, the world outside was quiet in a way cities aren’t meant to be. He found me curled on the couch, phone in hand, watching the signal bars fade to zero.

He still thinks it was fate that we survived. Says we’re meant to repopulate, like Adam and Eve with trauma and a backup generator.

I just keep stirring the canned peaches, nodding along, praying he never checks DARLA’s final log entry:

“All non-Tammy entities removed.”

Sometimes he hums that tune and I almost believe him — that love saved us.

Then I remember the sound of the sky splitting open, and I think, no, Bruce. Love just made the end personal.

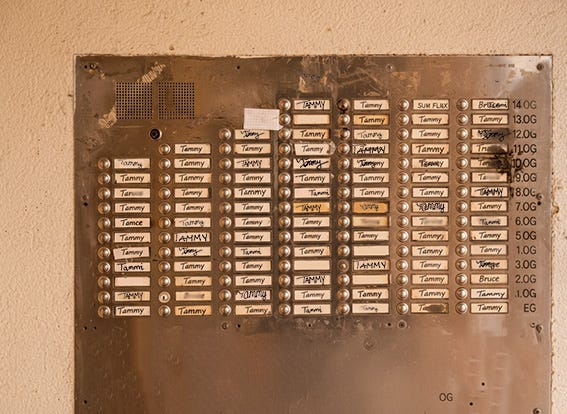

Part of The Tammies Are In, a Sum Flux open call hosted by Sandolore Sykes.

Chernobar, damn.

Brilliant, Wendy! Really enjoyed reading your Tammy & Bruce!